Evaluation of the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative’s Port Lands Flood Protection Project

Evaluation of the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative’s Port Lands Flood Protection Project

Evaluation of the Toronto

Waterfront Revitalization Initiative’s

Port Lands Flood Protection Project

(PDF Version) (1.91 MB)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Program Overview

- Evaluation Objective and Scope

- Summary of Key Findings

- Conclusions

- Annex A: Detailed Findings

- Key finding #1: The PLFP project supports the Government of Canada's continued environmental priorities, with a focus on resilience.

- Key finding #2: The PLFP project is making progress towards its expected outcomes.

- Key finding #3: Unexpected challenges pose a risk to project costs and timelines; however, Waterfront Toronto has managed to mitigate impacts to date.

- Key finding #4: The four-party project delivery mechanism is an efficient and effective model given the PLFP project’s type, scale and complexity.

- Key finding #5: The PLFP project is leveraging extensive engagement and best practices in order to create inclusive public spaces.

- Annex B: Methodology

List of Acronyms

AODA: Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act

CA: Contribution Agreement

CIP : Community Infrastructure Programs

ESC: Executive Steering Committee

FAA: Financial Administration Act

GBA+: Gender-Based Analysis Plus

IPI: Investment, Partnerships and Innovation

IGSC: Intergovernmental Steering Committee

MCFN: Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation

MOU: Memorandum of Understanding

MVVA: Michael Van Valkenburgh and Associates

OC: Oversight Committee

PLFP: Port Lands Flood Protection

PRB: Policy and Results Branch

TWG: Tri-Government Working Group

TWRI: Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative

TWRI: Waterfront Toronto’s Employment Initiative

Program Overview

Program description

The Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative (TWRI) was created in 1999 when the Governments of Canada and Ontario, and the City of Toronto, announced a plan to rebuild and renew the districts of West Don Lands, East Bayfront, and the Port Lands. This led to the creation of a designated waterfront area in the City of Toronto. Waterfront Toronto, a not-for-profit corporation with a Board of Directors appointed by the three levels of government, was established in 2001 with a 25-year mandate to lead the revitalization work.

Phase 1 of the TWRI included a commitment of $500 million each from the Governments of Canada and Ontario, and the City of Toronto. Phase 1 funding ended March 31, 2014, with all $500 million of federal funds spent by 2012-2013.

Phase 2 of the TWRI, Waterfront 2.0, was developed in response to the need for a comprehensive flood protection plan to advance the waterfront revitalization identified during Phase 1 of the TWRI. Phase 2 includes $1.185 billion in tri-government funding dedicated to the Port Lands Flood Protection (PLFP) project, with the federal contribution totaling $384 million. A Contribution Agreement (CA), signed by all three levels of governments and Waterfront Toronto, outlines the tripartite funding for the earthworks, infrastructure construction and public and park space creation and enhancements of this phase of the project and related expected outcomes. It also details the mechanisms for oversight, reporting and dispute resolution. Following the signing of this CA, the PLFP project began in 2017 and is expected to end in 2024.

Phase 2 was designed to protect approximately 240 hectares of land in southeastern portions of downtown Toronto that are at risk of flooding, and to remediate approximately 32 hectares of brownfields. Additionally, approximately 29 hectares of green space and 11 hectares of parkland will be available for public use. The PLFP project will also result in upgrades to municipal infrastructure in the area. This includes making improvements to roads, bridges, transit rights-of-way, and water and wastewater systems. In the long term, the project will provide opportunities for residential and commercial development, access to affordable housing, and public transit.

PLFP Project Outcomes

Immediate Outcomes

- Investments contribute to enhanced flood protection

- Investments contribute to the remediation of undeveloped brownfields

- Investments contribute to the practice of sound environmental processes of undeveloped brownfields

Intermediate Outcomes

- Investments contribute to enhanced storm water management

- Investments contribute to improved public access

- Investments contribute to enhanced critical infrastructure

- Investments contribute to improved environmental management of Toronto’s waterfront area

Final Outcomes

- Investments increase capacity to adapt to climate change impacts, natural disasters and extreme weather events

- Investments support more inclusive and accessible public spaces

- Investments increase opportunities for economic growth and development

Governance

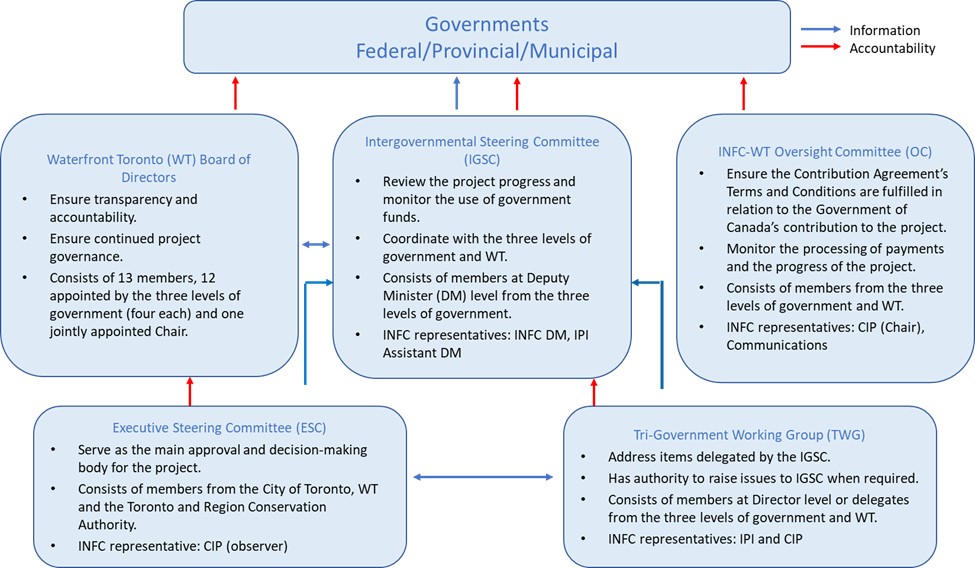

The three levels of government, along with Waterfront Toronto, make up a four-party mechanism responsible for the administration and governance of the PLFP project. Within INFC, the Investment, Partnerships and Innovation (IPI) Branch manages Waterfront Toronto (which, as a corporation, manages the broader waterfront revitalization project) and the Community Infrastructure Programs (CIP) Branch manages the PLFP project itself.

There are a number of governance committees, some of which oversee the broader waterfront revitalization issues and some of which focus specifically on PLFP. The governance structure is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1: INFC Governance for the PLFP Project

Text description for figure

Figure 1 shows the governance structure that supports the PLFP project:

- Waterfront Toronto Board of Directors: Ensure transparency, accountability, and continued project governance. Consists of 13 members, 12 appointed by the three levels of government (that is, 4 each) and one jointly appointed Chair.

- Intergovernmental Steering Committee (IGSC): Review the project progress and monitor the use of government funds. Coordinate with the three levels of government and Waterfront Toronto. Consists of members at the Deputy Minister (DM) level from the three levels of government. Within INFC , representatives are the Deputy Minister and the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Investments, Partnerships and Innovation Branches.

- INFC -Waterfront Toronto Oversight Committee: Ensure the Contributions greement’s Terms and Conditions are fulfilled in relation to the Government of Canada’s contribution to the project. Monitor the processing of payments and the progress of the project. The committee is composed of members from all three levels of government and Waterfront Toronto. INFC representatives are the Deputy Minister and the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Investments, Partnerships and Innovation Branch.

- Executive Steering Committee (ESC): Serve as the main approval and decision-making body for the project. The Executive Steering Committee consists of members from the City of Toronto, Waterfront Toronto and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. The INFC representative is from the Communities and Infrastructure Programs Branch and is an observer on this committee.

- Tri-Government Working Group (TWG): Address items delegated by the Intergovernmental Steering Committee and has the authority to raise issues to the IGSC when required. Consists of the Director level or delegates from the three levels of government. INFC is represented by both the Communities and Infrastructure Programs and Investments, Partnerships and Innovation Branches.

- All the committees in Figure 1 share information and are accountable to the federal, provincial and municipal governments.

There are also several other governance committees, mechanisms and working groups established between Waterfront Toronto and its other government partners, as well as those internal to Waterfront Toronto. INFC is invited to observe at some of these.

Evaluation Objective and Scope

Objective

The objective of the evaluation is to meet section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act (FAA) which requires an assessment every five years of all grants and contributions that exceed $5 million.

The evaluation covers issues of relevance and effectiveness as defined by the Treasury Board’s Policy on Results and related Directive:

- Relevance: the extent to which a program, policy or other entity addresses and is responsive to a demonstrable need. Relevance may also consider if a program, policy or other entity is a government priority or a federal responsibility.

- Effectiveness: the impacts of a program, policy or other entity, or the extent to which it is achieving its expected outcomes.

This evaluation also includes the government-wide commitment to include Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) in all evaluations as outlined in the Directive on Results.

Scope

The federal contribution in the timeframe required by the FAA obligation is for Phase 2 of the TWRI. This evaluation focuses on the PLFP project, the sole project under Phase 2 of the TWRI. The evaluation covers the period between April 1, 2017, and December 31, 2020, which is when the PLFP project began until the initiation of this evaluation.

Evaluation questions

The evaluation used three lines of evidence – document review, literature review and key informant interviews – to address the following questions:

Q1. To what extent does the PLFP project meet the needs to be addressed by the TWRI?

Q2. To what extent has progress been made towards expected outcomes for the PLFP project?

Q3. To what extent is this four-party project delivery mechanism efficient and effective?

Q4. To what extent has the design and implementation of the PLFP project incorporated inclusiveness?

Summary of Key Findings

Relevance

The project is well positioned under the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative and supports the Government of Canada's continued environmental priorities, with a focus on resilience.

Progress toward achievement of outcomes

The PLFP project is making progress toward its expected outcomes.

- Flood protection, brownfield remediation and river naturalization work is in progress and partially completed. Longer-term outcomes such as green infrastructure and green and public spaces are expected to be completed by the end of the project.

- There are some challenges with the selected performance measures and the ability to report on some of the indicators before project completion.

Unexpected challenges pose a risk to project costs and timelines; however, Waterfront Toronto has managed to mitigate impacts to date.

- Waterfront Toronto successfully managed the unexpected impacts of COVID-19 by mobilizing and responding quickly to new and evolving circumstances.

- Project partners are aware of the challenges and continue to monitor impacts to the project’s contingency.

Governance

The four-party project delivery mechanism is an efficient and effective model given the PLFP project’s type, scale and complexity.

Inclusivity

The PLFP project is leveraging extensive engagement and best practices in order to create inclusive public spaces.

- The PLFP project implementation includes employment initiatives that support a diverse workforce in jobs resulting directly from the project. The project also creates the foundation for future development plans that promise to include accessible and inclusive design.

- Public and Indigenous engagements for the PLFP project reflect best practices and have helped identify public priorities and support opportunities for Indigenous Peoples, namely the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, through the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

Conclusions

1. While it is still early in the PLFP project and work is ongoing, progress is being made towards expected outcomes.

The PLFP project’s CA does not require measurement of outcomes before the project is completed. A number of indicators for the project can only be fully measured upon project completion, making progress assessment challenging.

However, early data indicates there is progress towards addressing climate resilience needs through brownfield remediation and disaster mitigation in support of INFC and the TWRI’s objectives. As well, the creation of public spaces and infrastructure through the PLFP project will lay the groundwork for future development that aims to revitalize the Toronto waterfront in an accessible and inclusive manner. This aligns with recent commitments to support natural and hybrid infrastructure projects and help improve well-being, mitigate the impacts of climate change particularly on the most vulnerable, and prevent costly natural events.

2. The current governance structure is an effective mechanism for the delivery of a multi-partner project like the PLFP project.

The PLFP project’s multipartite governance structure has enabled coordination and communication amongst project partners that strongly supports the project’s progress so far and is warranted for a project of this type.

Specifically, with Waterfront Toronto as the delivery agent for the project, relationships have been facilitated and the delivery of mutually beneficial results in the context of a tri-government partnership has been enhanced.

3. Waterfront Toronto has demonstrated robust engagement practices with diverse audiences and Indigenous peoples that align with documented best practices and support inclusiveness.

Waterfront Toronto has developed expertise and knowledge in public engagement, and particularly in Indigenous engagement, that demonstrate an interest in and commitment to developing inclusive and community-driven projects. Waterfront Toronto’s Indigenous engagement may constitute a model to follow for future projects like the PLFP project. Its expertise in this area could continue to play an important role in future TWRI projects.

Annex A: Detailed Findings

Key finding #1: The PLFP project supports the Government of Canada's continued environmental priorities, with a focus on resilience.

Aerial view of the Port Lands 2008

Photo credit: Waterfront Toronto

The PLFP project outcomes broadly target climate change, economic, accessibility and inclusiveness objectives. These are in line with INFC’s mandate, particularly the focus on community resilience, and align with a current and documented need for climate-resilient infrastructure and flood protection able to respond to the increase of natural disasters due to climate change and other factors such as human interventions in natural habitats. To achieve these outcomes, the project includes brownfields remediation and redevelopment.

Text description of image1

The photograph depicts an aerial view of the Port Lands area and is dated 2008. The photograph is credited to Waterfront Toronto.

More specifically, the PLFP project is designed to address the need to protect 240 hectares of urban land that have historically been at risk of flooding. This includes extensive flooding under the Regulatory FloodFootnote1, due to heavy urbanization (over 80%) and development of the area prior to stormwater management control requirements. The project also intends to address significant human impacts on the Don River because of marsh/pond filling, removal of vegetation, rerouting of streams, and destruction of natural habitats.

The project is well positioned under the TWRI. As part of the broader initiative, the PLFP project is expected to result in land that is usable, sanitary and safe, allowing for public infrastructure and green spaces that achieve climate change objectives.

Key finding #2: The PLFP project is making progress towards its expected outcomes.

While it is too early to assess the achievement of long-term outcomes, some data for immediate and intermediate outcomes was available. Flood protection, brownfield remediation and river naturalization work is in progress and partially completed. Work on green infrastructure and green and public spaces is pending and is expected to be completed by the end of the project. As of December 31, 2020, the following results had been achieved: Footnote2

| IMMEDIATE OUTCOME INDICATORSFootnote3 | |

|---|---|

| Number of hectares of brownfields prepared for reuse (parkland, roads, new habitat) | (Target: 32 ha)

|

| Number of Environmental Approvals obtained (species at risk, Fisheries Act, navigation, Public Lands Act, etc.) | (Target: minimum of 4)

|

| Number of metres of protected shoreline | (Target: 6,000 lm)

|

| INTERMEDIATE OUTCOME INDICATORS | |

| Number of new bridges | (Target: 3 bridges)

|

| Number of metres of green infrastructure added | (Target: 2,800 m of armouring and valley walls)

|

| Number of linear metres of grade adjustments (raising) | (Target: 1.5 to 2 m of grade raising above existing)

*This does not translate directly into a linear measurement as various areas require different heights of fill to meet project goals. |

| Number of linear metres of new river channel added | (Target: 1,390 m of new river channel)

|

Text description of table1

Immediate and Intermediate Outcome Indicators – work in progress and partially completed

The following table presents immediate and intermediate outcomes indicators for which some results had been achieved by December 31, 2020, as well as the expected targets for these outcome indicators.

For the immediate outcome indicator for the number of hectares of brownfields prepared for reuse (parkland, roads and new habitat), the target is 32 hectares. It is noted that out of 1,369,119 cubic metres, 425,493 cubic metres (31 percent), of soil had been excavated within the project footprint of 46 hectares of brownfields. As well, 26,438 square metres out of 125,140 square metres (21 percent) of the horizontal environmental barrier system had been installed in the river valley.

Next, the table indicates that 5 out of the minimum target of 4 Environmental Approvals had been obtained. For the number of metres of protected shoreline, the table indicates that the target is 6,000 linear metres, and that 525 metres of shoreline had been protected, including 60 metres of dockwall reinforcement at the Cherry Street Bridge north abutment and 360 metres protected at Polson Slip).

Under the intermediate outcomes indicator for number of bridges, the target is of three bridges. It is noted that the design is complete for the two Cherry Street North bridges and the Cherry Street south bridge, and that all three are under construction. The first of the Cherry Street North bridges was delivered in November 2020. The design and construction of the Commissioners bridge are underway.

For the number of metres of green infrastructure added, the target is 2,800 of armouring and valley walls. The table indicates that 2,580 linear metres of cut off walls that define the new river valley had been completed and that neither the channel bio engineering or the Flood Protection Landform/Valley Wall Structures had been completed.

The table indicates that for linear metres of grade adjustments (raising), the target is 1.5 to 2 metres of grade raising above the existing grade. The table outlines that 127,339 cubic metres out of 998,014 cubic metres (13 percent) had been placed as fill to raise grades within the project footprint of 46 hectares of brownfields. It is noted that this does not translate directly into a linear measurement as various areas require different heights of fill to meet project goals.

Lastly, the table specifies a target of 1,390 metres of new river channel for the linear metres of new river channel added. The table specifies that 550 metres of the new river valley out of 1,513 metres (36 percent) has been added.

Some immediate and intermediate outcome indicators could not be assessed due to the following challenges:

| IMMEDIATE OUTCOME INDICATORS | |

|---|---|

| Number of hectares of land protected from flooding | (Target: 240 ha)

|

| Removal/altering of Special Policy Area designation of project zone (designates project area as a flood zone) | The Special Policy Area designation, as it pertains to the floodplain designation, cannot be removed in full until the new river valley is complete and connects the existing Don River to Lake Ontario through its new course. Additionally, the flood protection landform (located on Cadillac Fairview lands north of Lake Shore), the valley wall feature south of Lake Shore, and sediment and debris management area will need to be functionally complete to achieve flood protection and support the removal of the Special Policy Area designation. However, a phased removal of Special Policy Area designation could proceed as various components of work are completed. |

| INTERMEDIATE OUTCOME INDICATORS | |

| Number of linear metres of stormwater/ sewer added | (Targets: 2,550 m of storm sewer, 2,585 m of watermain and 2,008 m of gravity flow sewer)

|

| Number of hectares of public and green space added | (Target: 11 ha of parkland, 29 ha of green space, 13.1 km of water edge access)

|

| Number of hectares of habitat restoration | (Target: 30 ha)

|

Text description of table2

Immediate and Intermediate Outcomes Indicators – not assessed yet/pending

The table presents the immediate and intermediate outcomes indicators that could be assessed by December 31, 2020, along with the expected targets.

In terms of the immediate outcomes target of 240 hectares of land protected from flooding, the table indicates that the lands will be protected from flooding upon project completion scheduled for 2024.

For removal or altering of the Special Policy Area designation of the project zone that designates the area as prone to flooding, the table indicates that the Special Policy Area designation, as it pertains to the floodplain designation, cannot be removed in full until the new river valley is complete and connects the existing Don River to Lake Ontario through its new course. Additionally, the flood protection landform (located on Cadillac Fairview lands north of Lake Shore), the valley wall feature south of Lake Shore, and sediment and debris management area will need to be functionally complete to achieve flood protection and support the removal of the Special Policy Area designation. However, a phased removal of the Special Policy Area designation could proceed as various components of work are completed.

Under the intermediate outcomes heading, the table indicates the targets for the number of linear metres of stormwater and sewer to be added are of 2,550 metres of storm sewer, 2,585 metres of watermain and 2,008 metres of gravity flow sewer. The table notes that the sewers are under construction as of 2021. In terms of the number of hectares of public and green space added, the targets are of 11 hectares of parkland, 29 hectares of green space and 13.1 km of water edge access. The table specifies that public and green space will be one of the last components completed. Lastly, for the number of hectares of habitat restoration, the target is 30 hectares of habitation restoration, and the table indicates that no habitat has been restored so far using project funds.

Considerations for performance measurement

- The indicators chosen to measure project outcomes are inconsistent across program documents, causing some difficulties in matching reported results to the predefined outcomes in the CA. These internal discrepancies were noted by the CIP Branch who recently undertook to review and standardize these in consultation with INFC ’s Policy and Results Branch (PRB).

- Despite detailed and regular reporting, much of the progress data does not align with the outcome indicators from the CA. The CA did not require progress against outcomes measures to be reported prior to completion of the project and several project indicators can only be fully measured upon project completion, which makes measuring progress of the PLFP project challenging. However, Waterfront Toronto was able to provide and validate data on some of the performance measures in the CA upon request.

Examples of PLFP project achievements:

Designing and installing new bridges:

Cherry Street North bridge on its way

Photo credit: Waterfront Toronto

Text description of image2

The photograph depicts the Cherry Street North bridge on a barge while it travels toward Toronto from Nova Scotia in November 2020. The photograph is credited to Waterfront Toronto.

The design of the Cherry Street North, Cherry Street South and Commissioners Street bridges that will connect Villiers Island to the mainland was completed by the end of 2020. The first new bridge, the Cherry Street North bridge, traveled over 1,200 km on the Atlantic Ocean and St. Lawrence Seaway to get to Toronto from Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, arriving in November 2020. The design and engineering of the Port Lands bridges were recognized with a Special Jury Award for Catalytic Infrastructure at the 2019 Toronto Urban Design Awards.

An aquatic bird in the Port Lands area

Photo credit: Waterfront Toronto/Vid Ingelvics/Ryan Walker

Digging in the Port Lands

Photo Credit: Waterfront Toronto/Vid Ingelvics/Ryan Walker

Text description of image3

The first photograph shows an aquatic bird standing on rocks in the Port Lands area.

The second photograph shows a digger excavating a channel in the Port Lands area. Both photographs are credited to Waterfront Toronto, Vid Ingelvics and Ryan Walker.

Forming new collaborations for environmental and archeological monitoring:

In collaboration with the MCFN, Waterfront Toronto has been carefully protecting and monitoring ecosystems throughout the project to minimize the effects of lake filling and other work on wildlife. As well, it is working closely with the MCFN and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority to identify, recover and protect any artifacts uncovered during excavation work. This collaboration has been solidified in an MOU signed in 2020.

Key finding #3: Unexpected challenges pose a risk to project costs and timelines; however, Waterfront Toronto has managed to mitigate impacts to date.

Some challenges and inefficiencies posed risks to the project in terms of cost, schedule and scope, but Waterfront Toronto successfully navigated and resolved these unanticipated issues.

Cost and schedule uncertainties

In March 2020, the COVID-19 global pandemic created a climate of uncertainty with the potential to severely impact the PLFP project’s schedule and budget. Waterfront Toronto successfully managed this unexpected challenge and associated negative impacts by mobilizing and responding quickly to new and evolving circumstances. For example, in response to the shutdown of nonessential workplaces in Ontario in April 2020, Waterfront Toronto and EllisDon (construction manager) established the site as an essential construction workplace, thus ensuring that on-site work continued. Non-site project staff were able to work from home during this time. As well, when the city of Toronto stopped collecting permit applications temporarily in the spring of 2020, Waterfront Toronto worked successfully with the City of Toronto’s Waterfront Secretariat to continue its work. Lastly, as public engagement, public meetings and on-site archeological monitoring were suspended in the spring of 2020, Waterfront Toronto implemented interim measures and alternatives to maintain these activities. For example, smaller public meetings were held on Microsoft Teams and digital photos and video were used to record and share work for field liaison representatives from the MCFN to review for monitoring purposes. Sound mitigation strategies and regular and open communication between project partners on unanticipated issues as they arise have helped lessen cost and schedule uncertainties like the ones discussed here.

Potential implications

The rising costs due to COVID-19, as well as additional work and unexpected costs resulting from utilities relocation issues, have placed some added strain on the remaining contingency. As noted, communication is strong for the project, ensuring that all project partners are aware of this situation and able to monitor it closely.

Key finding #4: The four-party project delivery mechanism is an efficient and effective model given the PLFP project’s type, scale and complexity.

The four-party project delivery mechanism supports the delivery and implementation of the PLFP project, a complex infrastructure project with multiple partners, in a transparent, well-coordinated and effective manner.

While complex, the four-party governance structure is well suited to the PLFP project and aligns with best practices for multi-partner projects such as working within a formal agreement with the help of a facilitating agency; maintaining clear roles, responsibilities and expectations; and supporting regular communication through committees and other forums. All four parties agree that the governance structure is appropriate and efficient given the requirements of the project. The governance structure supports continuous and direct communication among the partners, as well as facilitating transparency of information and decision-making. For example, the ESC meets monthly and may identify issues to the IGSC as necessary. Interviews confirmed that documentation such as the CA and Terms and Conditions outline and define expectations, roles and responsibilities for the project, thus ensuring that these are clear and being implemented as planned.

There are some challenges internal to INFC with respect to the nested nature of the PLFP project within the larger Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative.

At times, there is some complexity and lack of clarity concerning internal responsibilities and committee relationships for the project. Indeed, the management of the PLFP project and the management of Waterfront Toronto are distinct yet related within INFC. Because the PLFP project – a CIP responsibility – is part of the broader TWRI that Waterfront Toronto – an IPI responsibility – oversees, there is some perceived overlap in responsibilities towards project management and project queries that involve Waterfront Toronto. As well, while the roles and responsibilities of the IGSC and the OC are defined in their respective governance documents, some interviewees expressed that the hierarchy and accountability relationships between these committees could be clearer. However, interviewees agreed overall that regular and open communication between CIP and IPI on these matters helps shed light on these situations. As well, these internal considerations did not have a visible impact on external partners.

Key finding #5: The PLFP project is leveraging extensive engagement and best practices in order to create inclusive public spaces.

GBA+ Considerations in Project Implementation

While project construction phases often lead to traditionally gendered employment opportunities (i.e., most construction positions are often filled by men), the PLFP project has resulted in direct positive employment impacts for women in this sector through targeted hiring by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), the lead landscape architect and designer for the project in 2020.

As well, Waterfront Toronto’s Employment Initiative (TWRI) and the MOU with the MCFN have also enabled employment and training opportunities for unemployed and underemployed individuals such as new immigrants, youth, and Indigenous people, thus supporting a more diverse workforce. The TWRI promotes employment opportunities at Waterfront Toronto, as well as connects unemployed and underemployed individuals to employment and training opportunities on projects like the PLFP. The MOU with the MCFN aims to create opportunities for participation in economic and commercial initiatives resulting from the PLFP and other waterfront projects. It also recognizes the need to offset costs related to MCFN’s meaningful participation in activities like environmental monitoring or working groups.

Indigenous Engagement

Overall, engagement with Indigenous communities and representatives for the PLFP project has been well received and demonstrates potential best practices for other projects. Waterfront Toronto has engaged with several Indigenous communities and organizations by providing regular updates and information since the start of the PLFP project, in alignment with the duty to consult delegated by the province of Ontario. In response to a 2018 Crown directive to seek a higher level of engagement with the MCFN as treaty holders for the project area, Waterfront Toronto signed a MOU in 2020. This MOU leverages best practices for Indigenous engagement and recommends establishing collaborative relationships. The MOU formalizes Waterfront Toronto’s relationship with the MCFN, outlining commitments to an Indigenous presence and an ongoing relationship with MCFN, as well as to employment opportunities, economic development and the continued celebration of Indigenous history and culture in the area through the PLFP and other waterfront projects.

Waterfront Toronto’s approach to Indigenous engagement emerges as exemplary because of its inclusive, holistic, open, respectful and knowledgeable stance towards Indigenous ways. Waterfront Toronto has actively incorporated Indigenous cultural frameworks and knowledge by, for example, working from the four directions, forming online sharing circles during COVID-19 and taking the time needed to engage properly and fully with Indigenous peoples and organizations. Indigenous project partners have received Waterfront Toronto’s efforts positively.

The ongoing relationship with MCFN has directly resulted in environmental and wildlife monitoring in the construction area and fish habitats, as well as archeological monitoring of the site during excavation. More recently, engagement has also involved design and creative components for the project. This has included discussions on the inclusion of cultural identifiers such as clan-based family structure identifiers, references to different Indigenous languages, the selection and landscaping of indigenous plants in habitat restoration areas, Indigenous involvement in calls for proposals and the selection of Indigenous artists for design elements.

Finally, future plans for development in the area include open spaces on Villiers Island that are expected to be inclusive and inviting for Indigenous peoples. These spaces will form an open, public ceremonial area by the water for various uses and ways to reconnect to the land and water.

Public Consultations and Engagement

Waterfront Toronto continued to build upon previous consultations that began in 2005 during the environmental assessment phase of the project. Over an 11-year span, Waterfront Toronto engaged with over 150,000 people by using a variety of forums and media such as detailed presentations, displays, in-person and virtual meetings, and stakeholder advisory and landowner and user committees. This broad public engagement helped reach diverse audiences and, from 5,300 initial comments, helped identify 183 consensus comments on public priorities such as affordable and accessible activities and housing, green space, and inclusive and accessible transit. The input from this public engagement serves as a key component of Waterfront Toronto’s design process and plans of public realms, particularly parks.

Having mostly reached middle-aged, higher income and white audiences in its initial public consultations, Waterfront Toronto held additional focus groups and workshops in 2019 with underrepresented groups such as youth, seniors and users outside downtown and east Toronto. These targeted consultations with underrepresented groups helped to further focus programming and design choices on needs such as park spaces for all ages, spaces and opportunities for socializing, accessible uses and public transportation. This reflects best practices for public engagement that seek to overcome systemic inequities by considering diverse representation and the existence of potential barriers to broader participation within a given community.

Waterfront Toronto continues to engage in public engagement and awareness through social media, newsletters, media releases and other platforms.

Future Considerations for Inclusive and Accessible Public Spaces

A theme of public access and inclusivity runs through the programming and design of future plans for development in newly remediated lands and developable lands created through the PLFP project. This project creates the foundation for future land development plans that aim to incorporate accessible and inclusive design and delivery. Plans are outlined in the Port Lands Planning Framework and the Villiers Island Precinct Plan and include mixed-use complete community with affordable housing, sustainable building and design, transit that connects the area to the rest of the city, and specialized playground equipment.

These plans align with documented strategies to make spaces more inclusive by diversifying their uses and research that shows that socially mixed neighbourhoods strengthen local economies and increase social cohesion. Future plans for the Toronto waterfront meet and may even surpass provincial Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) requirements. These plans outline expectations for diverse and accessible experiences, public areas, and parks that reflect best practices for accessibility, such as considering the physical aspects and materials of parks and accessible transportation to public and green spaces.

However, these plans are out of scope of the current project and there are no requirements in place to ensure that the design and development is implemented as intended. Given the documentation for PLFP has a strong emphasis on equitable and inclusive spaces in future development, and INFC is responsible for affordable housing initiatives, it would be in the Department’s interest to establish a mechanism to ensure that its support for creating developable space results in the desired outcomes beyond the completion of PLFP Phase 2.

Annex B: Methodology

Lines of Evidence

The three lines of evidence used for this evaluation draw on qualitative data (e.g., document review, literature review and key informant interviews) and some quantitative data (e.g., administrative and financial data). The analytical methods used for this evaluation were tailored to the nature of the data available. The evaluation design and level of effort were calibrated with available INFC resources. The following paragraphs describe the lines of evidence used for data collection as well as the limitations encountered during data collection and analysis, and the mitigation strategies used to address those limitations.

Document Review

The document review considered foundational project documents for context and an understanding of the need for the PLFP project as part of the broader TWRI, as well as the project’s governance structure and functioning. It examined documents that outline accessibility and inclusiveness measures in the design and delivery of the PLFP project and future development of land created and remediated as a result of the project. The document review also looked at evidence tracking and reporting on progress towards expected outcomes and any challenges that have affected project progress. There were some inconsistencies in the alignment and uniformity of progress data reported in project documentation compared to the outcome indicators chosen for the project, making it difficult to compare and report comprehensively on project progress so far. The data that was available was verified with both Waterfront Toronto and CIP and reported accordingly in findings. As well, the nested nature of the PLFP project within the TWRI meant that some of the documentation available for review reflected projects outside the scope of the PLFP project phase and therefore not funded under the PLFP Contribution Agreement. These overlaps in project documents required some filtering to parse out data that was relevant to the current evaluation only.

Literature Review

The literature review focused on the evaluation issue of design and delivery. It involved a scan of academic and policy literature on best practices for multiparty governance and project delivery and implementation approaches. This included examining best practices for public consultations, and accessibility and inclusiveness in infrastructure, parks and public space design. The literature review also explored how the project fit within a broader global context of documented disaster mitigation and climate resiliency needs. To fill a gap identified after interviews were conducted, a brief literature scan of Indigenous engagement best practices was added to supplement information on Indigenous engagement emerging from interviews with key stakeholders.

Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted to further contextualize and illuminate progress made toward outcomes and any challenges that affected project progress and the inner workings and effectiveness of the governance structure. Interviews also shed light on lessons learned related to project delivery and implementation so far, namely in terms of multiparty governance structures and Indigenous engagement. Interviews also provided more depth of understanding of Indigenous and public engagement, and inclusiveness dimensions of the PLFP project. Key informant groups included INFC officials, provincial and municipal representatives from the Oversight Committee, Waterfront Toronto staff, and members of Indigenous leadership that were involved in the engagement for the project. Although interviews with Indigenous participants were successful in providing added perspective on Indigenous engagement for the project, future evaluations involving Indigenous participants would benefit from more time to build relationships and trust. This documented best practice was reflected both in the literature review and in the feedback received from Indigenous interview participants.

Report a problem on this page

- Date modified: